Your purpose statement isn't working (Because you're doing it backwards)

Why organisational purpose fails to become personal meaning — And what to do about it

Organisations love a good purpose statement. They sit proudly on the website, appear in presentations beside emotionally-charged images of CEOs, and get referenced in town halls as a rallying cry to the masses.

Leadership talks about purpose with conviction. But when you walk through the organisation and ask people what it means to them, you normally get blank stares, some vague platitudes, or worse — rehearsed corporate language that carries no weight. No emotion.

The purpose is there. But it isn't working.

We've come to assume the problem is communication. Either not enough of it. Or just unclearly written or framed. So we refine the messaging, create more assets, cascade it through management layers, and hope it eventually "lands."

But the fundamental issue isn't communication at all. It's translation.

Just like the default communication flow - we end up defining purpose top-down, then expect it to automatically become meaningful to individuals. Declaring what matters, why the company exists, what it stands for — and assume that clarity at the organisational level creates clarity at the personal level.

It doesn't.

Because organisational purpose and personal purpose are not the same thing. And the gap between them is where most purpose-driven initiatives quietly fade to grey.

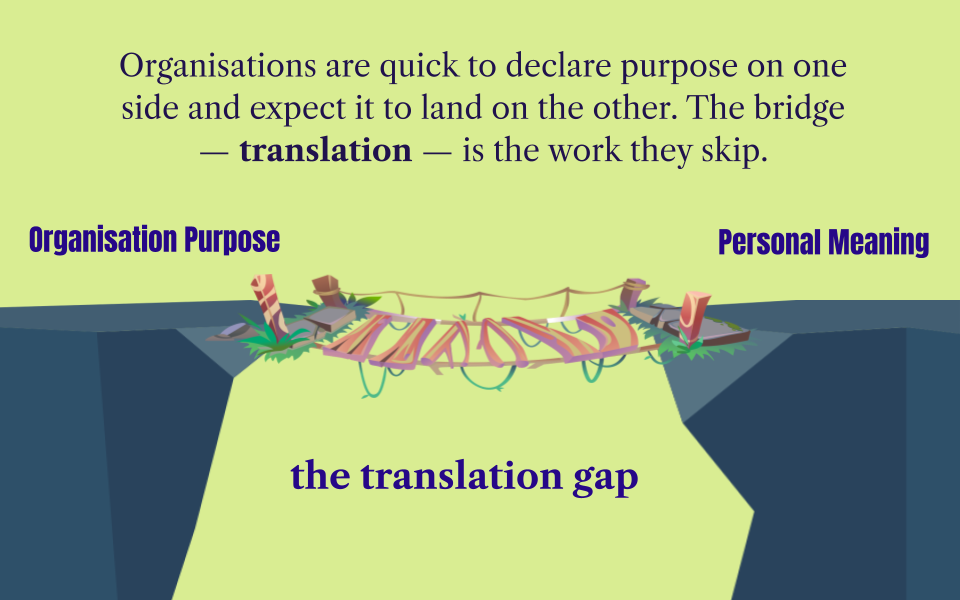

The Translation Gap

Here's what typically happens.

Leadership develops a purpose statement: "We exist to transform healthcare" or "We empower communities through technology" or "We're building a sustainable future." It's carefully crafted, aspirational, and sounds meaningful in the boardroom and to the shareholders.

Then it gets communicated. Presented. Explained. Leaders talk about it with passion, assuming that if they say it clearly enough, people will feel it.

But purpose doesn't work that way.

Purpose isn't a message you broadcast. It's meaning that has to be discovered, rebuilt, and made personal in each individual's world. The organisational purpose might be clear, but until someone can answer "What does this mean for my work, my identity, my daily decisions?" — it remains abstract.

This is the translation gap. The space between what the organisation declares and what individuals actually feel. And most leaders never do the work to bridge it.

They write the purpose statement. They don't help people translate it into their own lives.

Why translation matters more than declaration

Consider this insight from recent thinking on purpose-driven organisations: "It is not the company that defines purpose for individuals, but individuals who endow their work with a purpose."

Read that again.

The company doesn't grant purpose. Individuals create it. They take the work they do every day and connect it to something that matters — something that gives their effort meaning beyond a paycheck or a task list.

The role of a leader isn't to tell people what their purpose should be. It's to create the conditions where they can discover it themselves — within the frame of what the organisation is trying to accomplish.

This is harder than writing a purpose statement. It requires you to:

Understand what each person cares about

Help them see how their work connects to something larger

Give them language to articulate why it matters

Create space for them to make meaning, not just follow instructions

But we skip all of this. We declare the purpose and assume the work is done. Then we wonder why engagement scores don't move, why the culture feels disconnected, and why people quietly resist transformation efforts that should, on paper, inspire them.

The purpose didn't fail. The translation did.

The Backwards Model (And why it doesn't work)

Here's how most organisations approach purpose:

Step 1: Define the organisational purpose Leadership develops a statement about why the company exists, what it stands for, what it's trying to accomplish in the world.

Step 2: Communicate it The purpose gets packaged into presentations, internal campaigns, all-hands meetings. Leaders talk about it. HR reinforces it. Marketing uses it.

Step 3: Expect buy-in The assumption is that clear communication creates belief. If people understand the purpose, they'll connect to it. If they don't connect, the messaging needs to be clearer.

Step 4: Measure engagement Surveys ask: "Do you understand the company's purpose?" "Do you feel connected to it?" When scores are low, the response is more communication.

This model is backwards because it starts with the organisation and tries to push meaning outward. It treats purpose as something that can be transmitted, like information.

But purpose isn't information. It's meaning. And meaning can't be handed down — it has to be co-created.

The Forward Model (How purpose actually works)

Here's what should happen instead:

Step 1: Clarify the organisational frame Yes, define what the organisation stands for. But think of this as the frame, not the answer. It's the larger story people will locate themselves within — not the instruction for what they should feel.

Step 2: Ask the translation questions Before you communicate anything, ask yourself:

What does this mean to them? (Not to the board, not to leadership — to the person doing the work)

What problem does this solve in their world? (Not the market problem, not the strategic challenge — their actual daily frustration)

What becomes possible for them if they lean in? (Not for the company's growth targets — for their sense of identity, contribution, or impact)

If you can't answer these questions for different roles, functions, and individuals in your organisation, you're not ready to communicate the purpose yet.

Step 3: Create space for discovery Instead of telling people what the purpose means, help them discover it. Ask them:

What part of this work feels most meaningful to you?

When do you feel like what you're doing actually matters?

What would be lost if this work didn't happen?

These aren't rhetorical questions. They're the beginning of translation. They help people articulate their own "why" within the larger "why" of the organisation.

Step 4: Give them language Once people start to discover their own connection to the purpose, help them name it. Give them the language to articulate why their work matters — not in corporate speak, but in their own words.

This is where narrative design comes in. It provides the framework and context for creating the linguistic and conceptual tools that let people express what they're part of.

Step 5: Let purpose evolve Purpose isn't static. As individuals grow, as the organisation changes, as the world shifts — the connection between personal and organisational purpose will evolve. This isn't a failure of the original statement. It's the natural process of meaning-making.

The organisations that thrive are the ones that build this evolution into their culture, not the ones trying to freeze purpose in place.

What this means for leaders

If you're leading a purpose-driven organisation (or trying to become one), here's what you need to accept:

You can't manage purpose from the outside. Any attempt to dictate what people should care about will feel manipulative or paternalistic. Purpose is more than just packaging, or something people 'try on' - it's something people choose — freely, voluntarily, from within.

Your job isn't to inspire belief. It's to create the conditions where belief can emerge. Stop trying to "sell" the purpose. Start creating the space where people can discover why it matters to them.

Translation is the work most leaders skip — and it's the work that matters most. You can have the most compelling purpose statement in the world. If you don't help people translate it into their own lives, it will remain abstract. And abstract purposes don't drive behaviour, build culture, or sustain transformation.

The three translation questions (A practical framework)

Before you communicate your organisational purpose — whether it's to your entire company, a specific team, or an individual — ask these three questions:

1. What does this mean to them? (Not to you)

Get out of your own frame. Stop thinking about what the purpose means at the strategic level, the market level, the investor level. Think about what it means to the person sitting in front of you.

For a frontline employee, "transforming healthcare" might mean: "I can finally spend time with patients instead of fighting broken systems."

For a middle manager, it might mean: "I can lead a team doing work that actually helps people, not just hitting targets."

For an executive, it might mean: "I can build a legacy I'm proud of."

Same purpose. Different meanings. All valid.

2. What problem does this solve in their world? (Not yours)

You see the market opportunity. The competitive advantage. The strategic imperative.

They see: more work, more disruption, more uncertainty.

Translation means understanding the problem they're living with — the daily frustration, the thing that makes their work feel meaningless or exhausting — and showing them how the purpose addresses that.

3. What becomes possible for them if they lean in? (Not for the company)

Stop talking about company growth, market share, or shareholder value.

Talk about what becomes possible for them:

The work they've always wanted to do

The impact they've wanted to make

The person they want to become

When people can see themselves in the outcome — when they can imagine who they become by being part of this — that's when purpose stops being a statement and starts being a cause.

Why this matters now

We're entering an era where purpose isn't optional. Employees, especially younger generations, expect their work to mean something. They won't stay in organisations where purpose is just branding.

But here's the trap: most organisations respond by creating better purpose statements. More inspiring language. More compelling narratives, and lots more communication.

And it still doesn't work.

Because the problem was never the quality of the statement. It was the absence of translation.

Purpose-driven organisations are built by helping each person discover why it matters to them. By creating the conditions where meaning can emerge, evolve, and connect to something larger.

This is more than a communication problem. It's a design problem.

And it requires a different kind of leadership — one that understands that you can't hand people meaning. You have to help them find it.

What comes next

If you're serious about building a purpose-driven organisation, the next step isn't refining your purpose statement. It's asking:

Have we done the translation work?

Can every person in your organisation answer:

What does our purpose mean to me?

What problem does it solve in my world?

What becomes possible for me if I lean in?

If the answer is no — or if you're not sure — then you have work to do. Not communication work. Translation work.

And that's where narrative design comes in.

Because narrative design sits at the intersection of sense-making and emotional conviction. It's about creating the language, the frameworks, and the space where people can make sense of what they're part of — and connect it to what matters most to them.

That's the work most leaders skip.

And it's the work that determines whether your purpose becomes a banner on the wall — or a cause people carry forward.

About the Author

Hi — I'm Mike Lee. My discipline is designing the human engine of transformation: the confidence, connection, and ownership that makes strategy move.

I saw what happens when communication becomes reactive, when the story fades, and when the human system breaks under the weight of constant change.

And I realised: No one was designing the thing that matters most — the system of meaning that keeps people moving.

So I built a practice around the work I wished existed when I was inside the machine. Not communications as output, but communication as infrastructure. Not sense-making as garnish, but narrative and meaning as the spine of transformation.